|

|

|

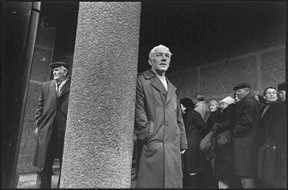

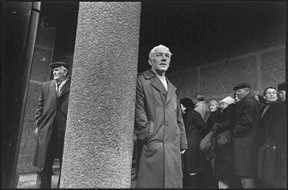

Days before, they had started lining up early in the morning outside the UNHCR's improvised safe

house. Hungry, they were waiting for bread. They were the old, those with nowhere to go, no strength to

travel, nothing left to lose. In the chaos of the Serbian exodus they had been left behind by their families as the most dispensable element,

occupying their apartments to prevent squatting by what they feared were the incoming Bosnian hordes.

Or they were simply people who, having lived through three wars, and having spent all their lives in

Sarajevo, had decided that this is where they would die. As usual, they were, along with the very young,

the primary victims of war, too feeble to run the snipers' gantlet, too tired to escape the uncertainty of peace.

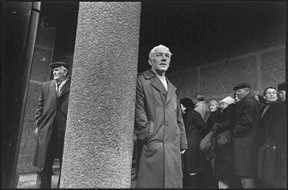

As the tides of war receded in the chaos of the last few days, glimpses of their existence during the

war were revealed. An ailing and aging couple had spent the four years of the war in an

apartment on the front line, having to enter through a hole in the wall and a meandering path through

the basement. Having survived it all, they had to evacuate their home on the last day of the siege

and watch it burn, losing in peace what they had managed to keep through the war.

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()