It was 23 years ago when I visited the White House. Having to call from the Washington airport, then arrive in a certain number of minutes for the Secret Service to know it was me, to get my security verified again upon arrival, my bag checked. It was impressive in those days, when only the Kennedy assassination nearly two decades before provided the nightmare. Now, with terrorists everywhere, that kind of security makes many people, I’m sure, nostalgic.

Reagan was President, and his personal photographer, Michael Evans, had asked if I would be interested in curating an exhibition of White House photographs. I agreed to look, and spent most of the day doing so. Lots of pictures of Reagan shaking hands with people. Not much interest. I decided to pass.

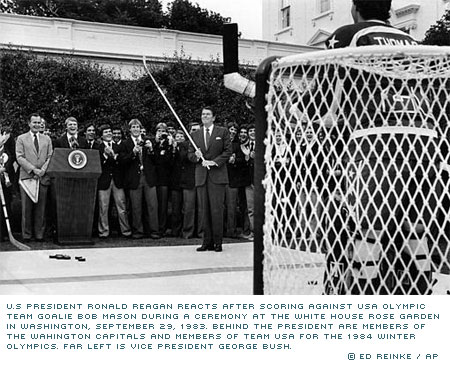

But I was impressed by the lunch with the white tablecloths, the china, the matchbooks with the official seal, all the busy staffers. But no Reagan? Where was he, I asked Michael at the end of the day? Practicing his hockey shot for when the US Olympic hockey team was scheduled to visit.

|

I thought he might be working on foreign policy, I said. But no, it was the hockey shot. Why? So he would look good for the media.

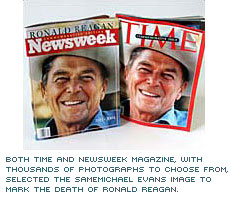

And as the New York Times reported this week on why both Time and Newsweek ran the exact same picture of Ronald Reagan on their respective covers – smiling, avuncular, with a white cowboy hat – the editors also published for the first time a photograph of Michael Evans, a Canadian, showing the President how to use a hockey stick while George Bush, Sr., and many others looked on. (And then on National Public Radio I heard a similar story, of Reagan throwing out the first ball at a baseball game. He had practiced with the Secret Service for three weeks before astounding the crowd with his ”spontaneous” skill.)

|

Many called John F. Kennedy the first television president. And, as we all remember, the Kennedy-Nixon radio debate was won by a tired, unshaven, Richard Nixon with dark rings under his eyes, whereas the television debate was won by the younger, more charismatic Kennedy. Kennedy, playing Camelot, was the adopted newcomer to national political office, representing a clan of touch-football playing achievers.

But Reagan was something more. He was not the politician who found his role on television, but the former actor who never stopped acting and now found his role as a politician. The forerunner of the Terminator turned Governor (cowboy replaced by cyborg), Reagan was the actor playing the man who even now, upon his death, is remembered for his genial disposition, his sense of humor, his human relationships. Somehow lost in the nostalgic glow is his once-upon-a-time role as the politician responsible for the greatest arms build-up in the history of the world, for the refusal to fund research against AIDS, for the Iran-Contra scandal, for “trickle-down” economics. He was and in death remained the “Teflon” president, invulnerable to much of the criticism, playing the folksy, genial politician, prone to forget, needing to be reminded (was it pre-Alzheimer’s?). Imagine Reagan with a Monica Lewinsky-style scandal – “Aw gee, it’s just one of those things that Nancy and I will have to straighten out” – emerging nearly unscathed.

Now, with the press apologetic for misreporting the non-existent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq before the war, for underplaying the pressure on the CIA to agree with the White House’s bellicose vision of Iraq, for taking at face value too much misinformation, the same press is now in a lather over the death of former President Reagan, leaving off much of the history of the politician to bask in the charm of the man.

I had another connection to Reagan. At the New York Times Magazine, where I was picture editor, we were doing one of those stories magazines seem to do too much on the first hundred days of the presidency. I needed to assign a photographer, and wanted one who did not know anything about the plaid-shirted, horse-riding, log-chopping Republican candidate in a cowboy hat who seemed to first want to be the Marlboro man and only then the president. I wanted to work with a photographer who could see what was behind it all, and I chose a foreign photographer who spoke no English. He was Sebastião Salgado, coming to the US from Australia where he was doing a story on the machine-gunning of Australia’s kangaroos. “What did you say to the President when you saw him?,” I asked Salgado, wondering what someone who spoke no English could accomplish. “Good morning, Mr. President, Good morning, Mr. President,” he told me. Even if it was the afternoon.

On the second day of Salgado’s three-day assignment the President was shot by John Hinckley. Salgado photographed the wounded President without knowing that he made the picture, on instinct, as if it was a war. In fact it was just as the Secret Service was pushing the President into his limo that the bullet hit the door and bounced into Reagan’s back. Until Reagan landed on the back seat even he did not know that he had been hit. Michael Evans, who was there, also did not at first know that his boss had been shot, and he did not recognize Reagan as the man being wheeled by him under a white sheet in the hospital. “Who is that?” Evans asked.

The New Yorker writer would later call these pictures by Salgado the only important pictures that he had taken among the 130 or so in the mid-life retrospective that I would curate in 1990. The rest, including the photographs of Latin American peasants, of Africans dying of famine, were too sentimental, too beautiful, too much “packaged caring.”

While Reagan was recuperating in the hospital the White House retouched out the intravenous tube connected to his arm so as to give him an image of more vitality. Reagan, the consummate actor, would play the part of recuperating president in good cheer and would, as if on cue, rise up again.

One more memory: While picture editor at the Times Magazine I had become frustrated with the difficulties, familiar to all picture editors, of convincing other editors and designers as to which were the strongest pictures. Many times there was opposition to certain photographs that I had found particularly interesting and provocative for reasons I could not fathom. So when Reagan was about to meet his arch-enemy, Mikhail Gorbachev, for the first time, I went to my editor-in-chief and suggested that this time it should be he who selects an image of each one of them. For once I would not choose, only to have my selections rejected. And, sure enough, in a matter of seconds this editor went through the two piles of pictures and selected a smiling Reagan and a scowling Gorbachev. He made it look easy.

Of course it turned out at the superpower meeting that Gorbachev was the charmer who would become the great liberalizer, and Reagan was distant and somewhat uncertain. But the folksy actor had to be cast a certain way, even by the nation’s paper of record.

When push comes to shove, the sure bet is Hollywood.

- Fred Ritchin

June 11, 2004