|

October

2000

This is Jill Freedman¹s first solo exhibition in New York since

she last showed her work at Witkin Gallery four years ago, and

an occasion to view a selection of 55 vintage prints selected

from her six photo-essays published in the last thirty years:

Old New: Resurrection City(1971), Circus Days (1975), Firehouse(1977),

Street Cops (1982), A Time That Was :Irish Moments(1987), and

Jill¹s Dogs (1993), as well as some previously unseen pictures.

For the viewer this mini-retrospective is an event, a rare occasion

to understand the full scope of Freedman¹s work and her rare

poetic gift that evokes the work of a painter like Alice Neel

by its compassion, wry humor and attention to the obscure and

the everyday.

For the first of her essays Freedman based herself in Resurrection

City and followed the Poor People¹s Campaign that took place

in Washington, D.C,.after Martin Luther King, Jr.¹s murder.By

living with her subjects she was able to record a story of community

and protest from an insider¹s point of view. Living with her

subjects for long periods of time and, even more than empathizing,

identifying with them completely, have been her tactics ever

since. Jill has the gift of losing herself in others so that

her pictures never seem contrived or posed: they are emanations

of the moment. Either people have completely forgotten about

her or she has been there for so long that they are not in the

least self-conscious when the camera clicks.This click is just

and extension of her being there.

|

|

|

|

Freedman who writes as well as she photographs explained about

her Irish pictures:²Today our vision of that country is coloured

by the violence of the North or the standard visual clichés:

freckled kids in Irish sweaters, all those green, green fields.

It¹s an older, gentler Ireland I am documenting. A wild and

passionate beauty that I feel is the last place on earth² .

Freedman helps us understand how pictures that look ³natural²

are in fact nothing like that.Their avoidance of cliché, magazine-like

prettiness and violence, their emphasis on grace and humor (

the pony drinking his pint at the pub, the goofy kids pulling

faces in front of a wall...) is in fact carefully, if not self-consciously,

accomplished. With grace Freedman walks a tight rope between

clichés and makes us forget about the void under her.

|

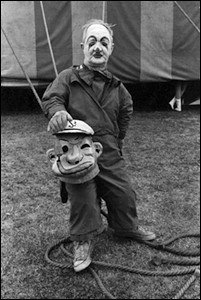

The

sad clown with a make-up smile, Serpentina the all-flexible

woman, Popeye the dwarf, the neighbors, the firefighters, the

children , the ponies, the elephants and the dogs, are, to paraphrase

Freedman ³us, only more.² They exist in the moment, totally

absorbed by who they are and what they are doing, Yet for all

her talent Jill Freedman, who started social documentary photography

roughly at the same time as Mary Ellen Mark and Annie Leibovitz,

has never achieved their cult status or their financial success.

She is admired by her peers but almost never mentioned by art

critics and historians. Maybe it¹s because, an independent person,

she did not abide by the cardinal rules of photojournalism:

photograph the victims, the beautiful and the famous. Or else

because she never strategized her career, did not capitalize

on what she had done. Rather, she went on to the next project

that captured her heart and stayed with it until she felt she

had rendered her subjects justice.

It is now high time for us to rediscover Freedman as the gypsy

daughter of the great Europeans from the humanistic tradition:

André Kertesz, Robert Doisneau, Willy Ronis and Edouard Boubat.

Carole Naggar |

|

Selected Works 1971-1993

Gallery@49 322 West 49th Street NY, NY 10019

(212) 767-0855

www.gallery49.com |

|

|

|